Dias eternos

In Venezuela, the criminal Justice System does not work equally for everybody. It takes away the Rights of the poorest and most vulnerable members of the society. Thousands of women, most awaiting trial and presumed innocent, are expected to be held for 45 days, but Venezuela’s crisis has rendered this notion a memory.

The situation inside the detention centers is a nightmare. They are dark, hot, overcrowded and claustrophobic. Prisoners receive no food, water or medical attention. Some are abandoned by their families and require help from the outside to survive.

Women are not separated from men (let alone transgenders and minors). There is no separation between convicted criminals and people awaiting trial. Pregnant women present infections and loss of placenta, a life threatening complication.

Living under these conditions does not allow rehabilitation nor reconciliation. “When we get out of here [the jail], if we do, we will be worse people than we were before prison”, said Yorkelis (21), who was detained two years ago. She calls “Chinatown”, a one-cell-only prison overcrowded with 60 women, her home.

Some of these women are victims of abuse in the family or coercion by men to commit a crime. The reason for their detentions are drug related, robbery or of political nature. Erika Palacios, is the first woman accused of the “Law against hate”, which forbids any protest against the government.

Faced with this dreadful prison reality, a mandatory task of public debate and political action in Venezuela and Latin American society must learn about the suffering of the incarcerated population in order to help remedy some of these problems. It is urgent to contribute to the urgent establishment of penitentiary institutions that do not violate the Human Rights of detainees.

This project was made with the support of the 2018 Women Photograph + Nikon grant and a Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting travel grant.

Días Eternos is the winner of Lucas Dolega International award in 2020, the LUMIX award for best photography series in 2020 and the 1st place of POY LATAM “the strength of women” category in 2019. Finalist of IWPA in 2020 and honorable mention of the PH museum women photograph grant in 2019. Shortlisted to the Getxo Photo Open Call in 2019.

It was part of a collective exhibition in the Organization of American States in Medellin, Colombia (2019). It was selected for the Festival Manifesto in Toulouse, France (2019) Photoville in New York (2020) and in the F3 Freiraum fur Fotografie as part of a collective exhibition selected from the LUMIX Photography festival for young photojournalism.

This series was published in the New York Times, Der Spiegel, El Pais newspaper, Dummy Magazine, Leica Fotografie International Magazine, Foto Femme United, Sueños de la Razón in the edition of Lucha y Poder, Tal Cual newspaper of Venezuela, Wordt Vervolgd and Reporters sans frontières.

In 2019, I delivered a keynote referring to these series in the Conference on Defending Human Rights hosted by the Florida Bar International Section Standing Committee in Public International Law, Human Rights and Global Justice.

Other interviews and online publications: One Photo One Story by Leica Fotografie International, Interview for the blog of Leica Fotografie International, interview and publication in Foto-Feminas.

VENEZUELA

In Venezuela, the criminal Justice System does not work equally for everybody. It takes away the Rights of the poorest and most vulnerable members of the society. Thousands of women, most awaiting trial and presumed innocent, are expected to be held for 45 days, but Venezuela’s crisis has rendered this notion a memory.

The situation inside the detention centers is a nightmare. They are dark, hot, overcrowded and claustrophobic. Prisoners receive no food, water or medical attention. Some are abandoned by their families and require help from the outside to survive.

El salvador

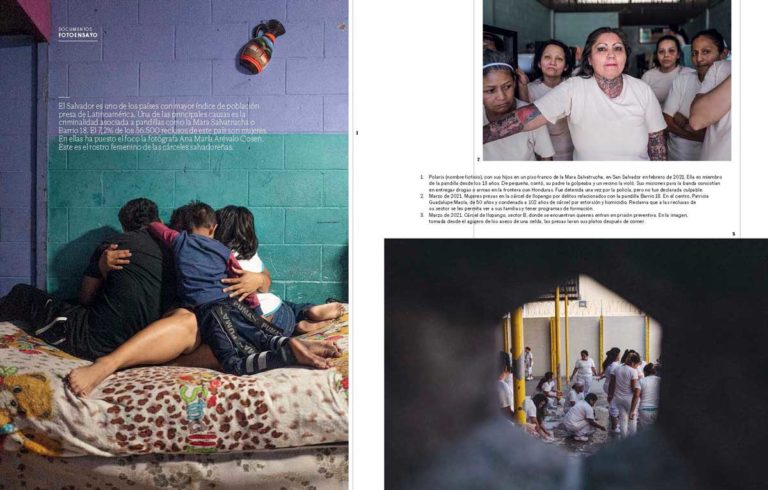

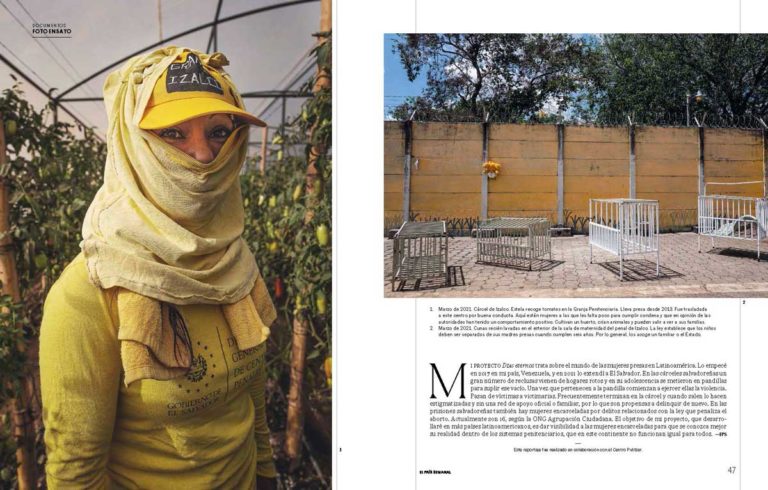

The destiny of imprisoned women in El Salvador has remained largely neglected and undiscussed. Imprisonment fuels crime and violence, destroys families, and affects the society through how criminals are judged, crimes are investigated, and minorities are treated.

Imprisonment disproportionality affects women as the breadwinner of their families. In El Salvador, abortion is punished with sentences up to thirty years. Alejandra was imprisoned for having a miscarriage when she was eight months pregnant. Her first daughter was one year old at the time. Alejandra served ten years. A year ago, her daughter passed away, “All those years lost in prison without being with her, and now I don’t have her.”

To escape from detention centers—hoping for a better life in state prison—many plead guilty, even the innocent ones. Guilty of abortion, gang membership, drug trafficking, or extortion. After conviction women become increasingly isolated, as they are not allowed to receive visitations or phone calls.

The penitentiary system lacks adequate support for women to be reintegrated into society. Without hope, jobs, and a supportive network of friends and family, women are likely to rejoin gang life or commit crimes after their release.

This project was done with the support of The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and published in El Pais Semanal in print and online